Notre Dame de la Garde, an elegant Roman Catholic basilica, has stood for 150 years on a promontory just south of Marseille’s Old Port, looking down protectively as fishermen push out to the sea and symbolizing the irrepressible spirit of this fabled Mediterranean city.

Notre Dame de la Garde, an elegant Roman Catholic basilica, has stood for 150 years on a promontory just south of Marseille’s Old Port, looking down protectively as fishermen push out to the sea and symbolizing the irrepressible spirit of this fabled Mediterranean city.

But a new and very different symbol is scheduled to rise soon on another promontory, this one on the north side of the Old Port. It is the $30 million Grand Mosque of Marseille, a place for the metropolitan region’s more than 200,000 Muslims to gather and worship and a dramatic reminder of the Islamic heritage that is grafting itself onto France’s cultural landscape.

The mosque, which at 92,500 square feet will be France’s largest, has become an emblem for the many native French people who feel uncomfortable with an immigrant population that, as its numbers rise, increasingly seeks to live by its own religious and cultural rules rather than assimilate into France’s long Christian tradition.

The strain is particularly intense in Marseille, where kebab shops line the once-elegant Canebiere Avenue and North African Arabic seems as prevalent as French on the sunny cafe terraces where residents traditionally do their business and take their aperitifs. But Marseille is not alone; across the wealthy countries of Western Europe, growing communities of Muslim immigrants have created unease among native populations by seeking to affirm their own identities – by building mosques, for instance, or wearing veils in the street.

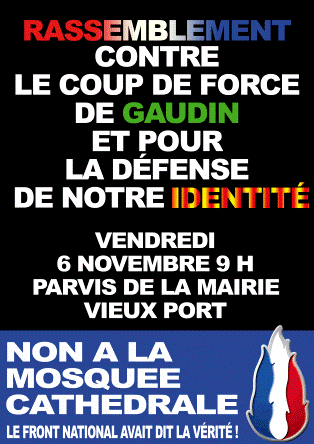

Ronald Perdomo, a right-wing lawyer and Marseille politician, called the planned mosque a “cathedral mosque” designed to be a “symbol of non-assimilation” that will balance off Notre Dame de la Garde and send a message from its 75-foot-high minaret that Marseille’s Muslim residents are “imposing their religious norms.”

After failing in two lawsuits to block a construction permit for the mosque, Perdomo’s Regional Front and three other rightist groups filed a new suit Tuesday alleging that Mayor Jean-Claude Gaudin sidestepped building regulations in granting the permit and thus violated the constitutional separation of church and state.

A native French retiree polishing his car near where work on the mosque is scheduled to begin in April lamented the project. But the mosque, he said, is only part of what Muslim immigrants have done to Marseille in recent years. Speaking on the condition of anonymity, he said he did not want to be racist, “but you have to, when you see what is happening.”

“Marseille is finished,” he added, before turning to a game of petanque. “There is nothing left but blacks and Arabs.”