Jamaat-e-Islami demonstration against Israel’s attack on Gaza

Under the heading “Bangladesh set to become again a secular state”, left-wing blogger Andrew Coates has enthusiastically hailed what he claims is a decision by the government of Bangladesh to restore the secular foundations of the country’s constitution.

He bases his post on reports that the Supreme Court in Dhaka has upheld a ruling that the government can reverse amendments made to the constitution in the period following the military coup of 1975. Coates approvingly quotes law minister Shafique Ahmed as saying: “In the light of the verdict, the secular constitution of 1972 already stands to have been revived. Now we don’t have any bar to return to the four state principles of democracy, nationalism, secularism and socialism as had been heralded in the 1972 statute of the state.”

There were indeed amendments made to the 1972 constitution after 1975 that undermined the secular basis of the state. The religious invocation “Bismillah-ar-Rahman-ar-Rahim” (“In the Name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful”) was added to the preamble of the constitution, and Islam was declared to be the official state religion of Bangladesh. To overturn those amendments would of course be entirely legitimate from the standpoint of establishing a secular state, and if the government of Bangladesh were proposing to change the constitution accordingly there would be no objection.

However, the government has shown little enthusiasm for such a change. Following a meeting last month between the ruling Awami League and its coalition partners, one of whom urged that the constitution should be amended along those lines, prime minister Sheikh Hasina stated firmly that the words “Bismillah-ar-Rahman-ar-Rahim” would be left unchanged in the constitution, as would the declaration that Islam is the state religion.

It is not difficult to identify the motive behind this decision. During the 2008 election campaign the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and its Islamist ally Jamaat-e-Islami accused the Awami League of hostility towards Islam, and Sheikh Hasina no doubt reasons that if her government were to abolish the religious elements in the constitution this would be exploited by the opposition. So an entirely justifiable change that would restore the secular principle to the constitution has been rejected on pragmatic, not to say opportunistic, political grounds.

What, then, are the “secular foundations” of the 1972 constitution that the Bangladesh government wishes to restore? Well, crucially they want to reinstate a provision, subsequently removed, which declared that “no person shall have the right to form, or be a member or otherwise take part in the activities of, any communal or other association or union which in the name or on the basis of any religion has for its object, or pursues, a political purpose”.

Indeed, following the Supreme Court’s verdict, Shafique Ahmed was quoted as saying that all religion-based parties should “drop the name of Islam from their name and stop using religion during campaigning”, and he went on to announce that religion-based parties are going to be “banned”. In short, what the government of Bangladesh is planning to do is to amend the constitution in order to illegalise Jamaat-e-Islami.

What does this have to do with secularism? Nothing whatsoever. If a secular constitution required the suppression of faith-based political parties, then secularism in Germany would require a ban on the Christian Democrats. And nobody, not even a secularist ultra like Andrew Coates, is calling for that.

You can imagine how different the response would be if a government headed by Jamaat-e-Islami were to propose a ban on secular parties in Bangladesh, on the grounds that they conflicted with the Islamic basis of the constitution. Coates, along with the likes of Harry’s Place and the Spittoon, would be furiously denouncing “totalitarian Islamism” and its contempt for democratic principles. But a secular party proposes to ban an Islamist party and you don’t hear a peep from them.

Olivier Besancenot, the postman-turned-revolutionary at the helm of France’s anti-capitalist movement, has been fiercely criticised from all sides of the political spectrum for

Olivier Besancenot, the postman-turned-revolutionary at the helm of France’s anti-capitalist movement, has been fiercely criticised from all sides of the political spectrum for  “Just when it seemed that Republicans in America had a monopoly on Islamophobic hysteria, the Sunday Times prompted a torrent of similar hysteria in the UK by running an article in which an employee of Amnesty International – Gita Sahgal, head of the gender unit at the International Secretariat – criticized the organization that employed her for its association with former Guantánamo prisoner Moazzam Begg.

“Just when it seemed that Republicans in America had a monopoly on Islamophobic hysteria, the Sunday Times prompted a torrent of similar hysteria in the UK by running an article in which an employee of Amnesty International – Gita Sahgal, head of the gender unit at the International Secretariat – criticized the organization that employed her for its association with former Guantánamo prisoner Moazzam Begg. A senior official at Amnesty International has accused the charity of putting the human rights of Al-Qaeda terror suspects above those of their victims.

A senior official at Amnesty International has accused the charity of putting the human rights of Al-Qaeda terror suspects above those of their victims.

“Islam doesn’t demand that men cover their faces before they go out, but its more extreme advocates place special conditions on how women dress outside the home. It’s a typical example of patriarchal practice, based on the notion that women should be under the control of their male relatives at all times, and it’s incompatible with any notion of universal human rights….

“Islam doesn’t demand that men cover their faces before they go out, but its more extreme advocates place special conditions on how women dress outside the home. It’s a typical example of patriarchal practice, based on the notion that women should be under the control of their male relatives at all times, and it’s incompatible with any notion of universal human rights….

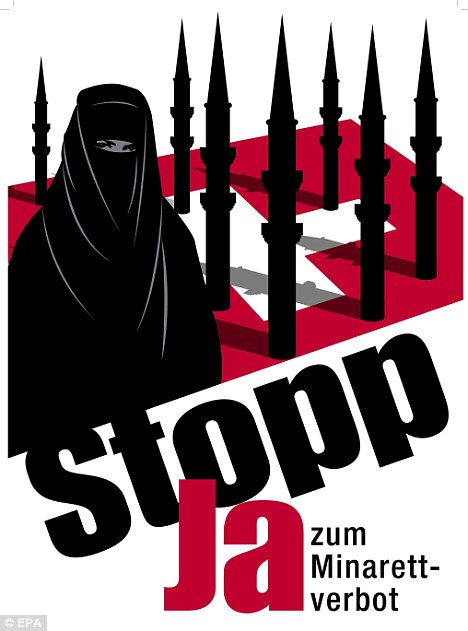

Joan Smith offers her profound thoughts on the result of the Swiss referendum:

Joan Smith offers her profound thoughts on the result of the Swiss referendum: