Sara Korvel has a lot to offer prospective employers: a recent graduate of a major university, she made the dean’s list in seven of eight semesters and belongs to the Phi Beta Kappa honors society. Fluent in four languages, she landed prestigious internships at an international bank and a state public broadcaster, and held down a job as a Starbucks shift manager for most of her college career.

Sara Korvel has a lot to offer prospective employers: a recent graduate of a major university, she made the dean’s list in seven of eight semesters and belongs to the Phi Beta Kappa honors society. Fluent in four languages, she landed prestigious internships at an international bank and a state public broadcaster, and held down a job as a Starbucks shift manager for most of her college career.

Sara has one significant factor working against her as she searches for her first post-college job, though: she’s a Muslim.

A pair of studies by University of Connecticut researchers have discovered that employers are demonstrably less likely to respond to a job application if that resume includes evidence of membership in a faith group. And far and away, the faith group employers least want to engage is Islam.

“What we found is that, when applying for a job, it’s better not to mention religion at all – but employers really don’t want you to mention being a Muslim,” said professor of sociology Michael Wallace, who conducted the studies along with Bradley Wright, an associate professor in the sociology department.

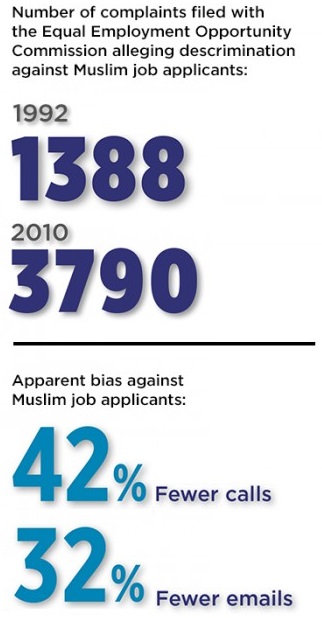

The two studies – one published in the journal Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, and the other published in Social Currents – aimed to examine religious discrimination, which has reportedly been on the rise: between 1992 and 2010, the number of complaints filed with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission alleging such discrimination grew from 1,388 to 3,790.

Wallace and Wright created resumes on behalf of four fictional recent college graduates (including the high-achieving Sara Korvel). Using a popular job-listing website, they sent four applications at a time to employers, taking care to make the resumes – which were reviewed in advance by human resources professionals – different enough not to arouse suspicion.

Each resume was randomly assigned an identity based on religious preference – Catholic, evangelical Christian, atheist, Jewish, Muslim, pagan, and “Wallonian,” a fictional faith – or was designated part of a control group that had no religious affiliation at all.

Since the resumes were all purportedly from recent graduates of major public universities, religious belief could be introduced unobtrusively under the banner of extracurricular activities. Each fictitious job seeker was therefore listed as an officer in the “Muslim Student Group” or the “Campus Jewish Association,” except for the control group, whose resumes listed them as belonging merely to the “Student Association” or something similar.

For the first study, the researchers sent out 6,400 applications to 1,600 job postings in New England, setting up eight voicemail boxes and eight separate email addresses to collect the responses.

Wallace and Wright expected the control group to get the most responses, based on “secularization theory”: even though Americans consistently profess a high degree of religiosity, religion is increasingly seen as a purely private matter, and public expression of it – such as in the workplace – is likely to be frowned on.

The results bore that out in the New England study: applicants expressing any religious identification received 19 percent fewer overall contacts than the applicants from the non-religious control group.

What the researchers did not expect, though, was the scope of the apparent bias against Muslim applicants: Muslims received 32 percent fewer emails and 48 percent fewer phone calls than applicants from the control group, far outweighing measurable bias against the other faith groups.

“Just by adding the word ‘Muslim’ to an application, its chances of receiving an employer contact were reduced by between a third and almost half,” Wright said.

Curious to see if this would be the case elsewhere in the country, the researchers replicated the study in the South. By measures like church attendance and belief in God, the South is significantly more religious than New England, and has a much larger evangelical Christian population, and Wallace and Wright wondered how this would affect the results.

The researchers sent out 3,200 applications to employers within 150 miles of two major Southern cities and found that, when it comes to religious bias, Southern employers have much in common with their New England counterparts.

The Southern study found that religious resumes received 29 percent fewer emails and 33 percent fewer phone calls than the control-group resumes; but Muslim applications got 38 percent fewer emails and 54 percent fewer phone calls than the non-religious control group, and were less likely to get a response than those with any other religious indicator.

The major difference between the two regions was that Southern employers were also more likely to discriminate against other religious groups, particularly atheists, pagans, Catholics, and the fictitious Wallonians. Somewhat surprisingly, Jewish applications fared well in the South, almost matching the response rate for the non-religious control group.

“There’s been a growing discussion about religious discrimination in the workplace, but very little of it has been about Muslims,” Wallace said. “What these studies suggest is that there’s a reluctance to even engage job applicants who might be Muslim just because they’re Muslim, which should give anyone who cares about equal opportunity cause for concern.”