The Czech Republic experienced a spike in Islamophobia in 2014 despite there being a very small number of Muslims in the country, Petr Zídek writes in the daily Lidové noviny (LN) today.

The Czech Republic experienced a spike in Islamophobia in 2014 despite there being a very small number of Muslims in the country, Petr Zídek writes in the daily Lidové noviny (LN) today.

Although President Milos Zeman’s popularity plummeted in the past year, he is still highly respected by Islamophobes, Zídek writes.

In mid-December, the Islamophobes wrote a letter to Zeman in which they praised his open “objections to the Islamic theocratic and totalitarian ideology.” They highly appreciated Zeman for opposing “the efforts by influential groups in Czech and European society to pursue a policy of appeasement towards this old-new totalitarian threat.”

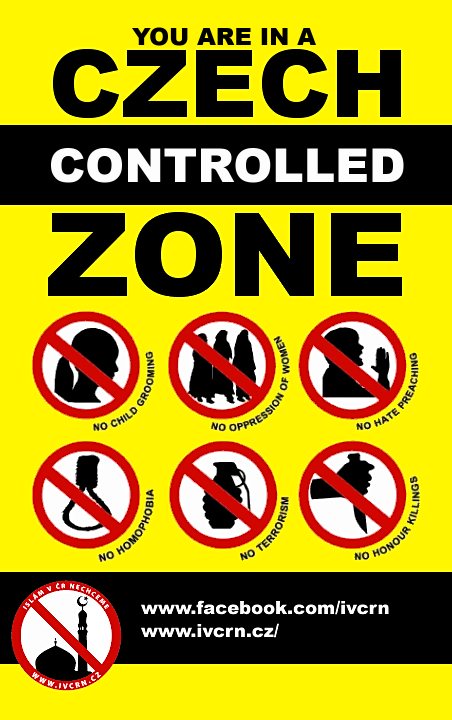

Leaders of the anti-Islam initiative, which has more than 93,000 supporters on Facebook, have asked Zeman to veto a planned bill that is to extend the powers of the ombudsman. They criticize the current ombudsman, Anna Šabatová, for having defended two female Muslim students whom a Czech secondary school did not permit to wear head scarves earlier this year, Zídek writes.

The Czech Islamophobes fail to understand that the core of the dispute was not Islam and its habits but the question of whether school rules may be at variance with the constitution, Zídek writes.

The Islamphobes say if the ombudsman’s powers were extended, Šabatová would use her new powers to “persecute the critics of Islam and thereby strengthen the presence of Islam in the Czech Republic,” Zídek quoting them as saying.

Earlier in 2014, Islamophobia was for the first time widely used as an instrument in the campaign before municipal elections. Even in one district in Prague, otherwise a cosmopolitan city, the highest number of preferential votes went to the then-deputy mayor who presented the stopping of a Muslim cemetery project as her biggest success in the past election period, Zídek writes.

A noteworthy aspect of Czech Islamophobia is that it can easily do without Muslims, he continues. The number of supporters of the “We Don’t Want Islam in the Czech Republic” group is at least five times higher than the estimated number (20,000) of Muslims living in the Czech Republic, whose population is some 10.5 million, Zídek writes.

According to the last census, only 1,442 people claim adherence to the Czech Muslim Community (UMO), a mere fraction compared with, for example, the Jehovah’s Witnesses group with 13,000 adherents, Zídek writes.

For Czech Islamophobes, news about the Islamic State (also known as ISIS, ISIL or Daesh) and from the West European countries with strong Muslim minorities is enough to foment hatred in the Czech Republic, he says.

In this atmosphere, a positive step is Bronislav Ostranský’s book Atlas muslimských strašáků (Muslim Scarecrows Atlas), which the Academia publisher’s house issued recently.

The book is a useful introduction to Islamic Studies, because it corrects certain widespread clichés. It points out, for example, that only 25 percent of Muslims are Arabs, that jihad is not a mere appeal for violence and that female circumcision has almost nothing to do with Islam, Zídek writes.

However, staunch Islamophobes will hardly “yield” to rational arguments. The Muslim terrorists have just killed another person, and Islam wants to destroy our civilization, they would say, referring to TV newscasts, Zídek writes.

Maybe the time has come to launch a new initiative, “We Don’t Want Islamophobia in the Czech Republic,” he concludes.