A Muslim woman wearing a hijab put the Parti Québécois on the defensive in a sharp exchange on the first day of hearings over the secular charter that would prohibit public sector employees from wearing overt religious symbols.

A Muslim woman wearing a hijab put the Parti Québécois on the defensive in a sharp exchange on the first day of hearings over the secular charter that would prohibit public sector employees from wearing overt religious symbols.

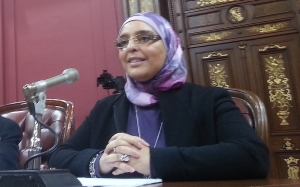

Samira Laouni told the minority PQ government that its proposed legislation was creating social tensions unheard of in Quebec until now. Some Muslim women have been spat on and have had their head scarf torn off, she said. “I’ve been here for 15 years. I have never seen it like this until now,” she told the committee.

Ms. Laouni was among the first seven to appear at the National Assembly, but 250 parties have submitted briefs and 200 hours have been set aside for presentations over the next several weeks.

The issue has divided Quebeckers, and opposition parties accuse the PQ of trying to take advantage of the storm of protest to attract enough voter support, especially in predominantly francophone ridings, to win a majority government in an election many expect will be held this spring.

The PQ minister responsible for democratic institutions, Bernard Drainville, went to great lengths to defend the bill he tabled last November. He argued that only 20 per cent of Muslim women in Quebec wear the veil. “That is one in five that won’t be affected by the restrictive measures,” he said.

Ms. Laouni lashed back by reminding the minister that it was his responsibility to protect minorities. “In a democratic country you need to think about the 1 per cent that is affected. You don’t think about the absolute majority, you think about the minority that is being crushed,” she said.

Throughout the hearings Mr. Drainville argued that his role was to stand up for average citizens who have a right to be served by religiously neutral public service. Some of those who appeared before the committee on Tuesday agreed with the minister, including René Tawani, an Egyptian-born University of Montreal professor who argued that the veil was a religious symbol imposed on women by Muslim fundamentalists in recent years for strictly political reasons.

“What is the true motive behind the veil?” asked Mr. Tawani. After all, the veil didn’t exist 20 years ago, yet Islam has existed for 1,400 years, he said.

In the face of Ms. Laouni’s arguments, the PQ government was at a loss to explain how it had no studies to support its claim that wearing religious symbols impeded the neutrality of a public servant’s duties. “It is odious to demand that people take off their religious symbols during work hours because it places them before a heart-wrenching decision: accept to work or renounce their identity.”

Ms. Laouni, who founded an organization promoting closer ties among cultural groups, said she supported several proposals in the bill, including the need for Quebec public institutions to be secular and defend gender equality. She also approves of the ban for public servants in positions of authority, such as police and judges. She added that the government should also adopt guidelines to help public institutions handle demands for religious accommodations. “But we absolutely, firmly and categorically reject the prohibition of anyone wearing a religious symbol as being part of their faith and their identity,” she said.

Mr. Drainville insisted that Ms. Laouni explain why, in spite of her firm opposition to the ban on religious symbols, she was willing to make exceptions.

“Why would it be acceptable for you to prohibit police, judges or prison guards from displaying religious symbols and not others?” the minister asked.

“The answer is simple; it’s the uniform,” Ms. Laouni responded. She added, tongue in cheek: “Maybe Quebec will end up with a Mao Zedong dress code … and then there won’t be any more problems.”

The PQ was clear that it would maintain a ban on religious symbols in the public service and wasn’t inclined to make any compromises.

Without a consensus in sight, opposition parties fear the hearings may only serve to further polarize an already divisive debate on the secular charter bill. With the Liberal showing signs of division within their ranks over the ban on religious symbols and the Coalition Avenir Québec competing to have its voice heard in favour of a more moderate ban, the minority PQ government appears willing to allow the debate to pursue its course and eventually decide whether to call an election and ask voters to choose.

“We will try to reach an agreement with the CAQ. But if we can’t and an election is called, it will be up to voters to decide,” Mr. Drainville said earlier this week.