In April, the chair of the Charity Commission told The Sunday Times: “The problem of Islamist extremism is not the most widespread problem we face in terms of abuse of charities, but is potentially the most deadly. And it is, alas, growing.”

In April, the chair of the Charity Commission told The Sunday Times: “The problem of Islamist extremism is not the most widespread problem we face in terms of abuse of charities, but is potentially the most deadly. And it is, alas, growing.”

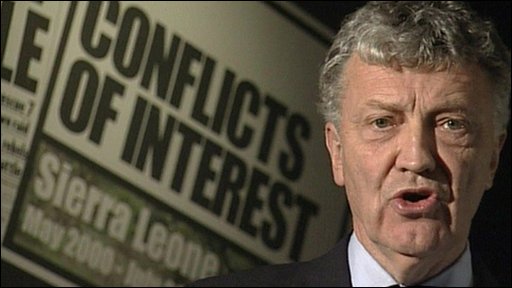

William Shawcross might have had in mind Abdul Waheed Majeed, who travelled from the UK with a charity aid convoy to Syria and drove a truck packed with explosives into the wall of a prison in Aleppo in February. This was believed to be the first suicide attack carried out in Syria by a Briton, but whether this on its own justifies the “most deadly” assessment is up for debate.

Since February, the Charity Commission has hosted meetings for charities that work in Syria, joined a national police campaign to protect young people from the dangers of travelling there and issued 10 tips to help Muslims give safely during Ramadan. It has also opened monitoring cases and statutory inquiries into Muslim charities working in Syria, and into other Muslim charities.

Of the 20 most recent statutory inquiries announced by the commission, five involved Muslim charities. This is hugely disproportionate: out of more than 180,000 charities registered with the commission, there are perhaps 2,000 that can be defined as Muslim or Islamic.

It is hard to see where risk-based monitoring ends and bias begins. The accusation of bias was raised by Sir Stephen Bubb, head of the charity leaders group Acevo, who said last month that the chief executives of Islamic Relief and Muslim Aid, and the head of the Muslim Charities Forum, had told him the regulator was “targeting Muslim charities in a disproportionate way”.

Bubb said: “In the turbulent world we live in, we are aware of terrorist threats from many parts of the globe. But if it raises perceptions of a bias then that is in itself a problem. Perception is neither true nor false – it’s a perception – but damage can be done to charitable giving through bad perceptions.”

Anti-Islamic perceptions might be reinforced by these facts: in 2005 Shawcross wrote a book called Allies: Why the West Had to Remove Saddam; Peter Clarke, a member of the commission’s board, led the government inquiry into the alleged “Trojan Horse” plot in Birmingham schools; and fellow board member Nazo Moosa’s departure next month will further reduce ethnic diversity among senior figures at the commission.

Cage, a body that works with communities affected by the war on terror, has also alleged institutional bias by organisations including the commission, which has opened monitoring cases into the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust and the Roddick Foundation over the funding they give to Cage.

Amandla Thomas-Johnson, the communications officer at Cage, says: “Our issue is their brushstroke treatment of Muslim organisations. Shawcross came out in April saying there’s a real problem with Islamic extremism – and you’ve got to ask, what does that really mean?”

Thomas-Johnson cites research that Muslims are the most charitable community in the UK, and says: “You’re in effect stopping money from going to causes that are worthwhile, and I think that’s very irresponsible.”

This month, Sir Stephen Etherington, chief executive of the National Council for Voluntary Organisations, is also to meet a number of Muslim charities to discuss the commission’s approach. “We will take forward any issues that arise from the meeting with the commission,” he says.

The controversy over the commission’s relationship with the Muslim community is clearly going to continue: to borrow Shawcross’s language, this might not be its most widespread issue, but it is potentially its most delicate.

See also “Islamic extremism a ‘deadly’ problem for charities, William Shawcross says”, Islamophobia Watch, 20 April 2014

And “William Shawcross – the neocon, Zionist, anti-Muslim head of the Charity Commission”, Coolness of Hind, 4 April 2014