A new study into the effects of the “Trojan horse” scandal in Birmingham finds 90 per cent of the city’s Muslims feel community cohesion has been damaged by the way the affair was handled.

A new study into the effects of the “Trojan horse” scandal in Birmingham finds 90 per cent of the city’s Muslims feel community cohesion has been damaged by the way the affair was handled.

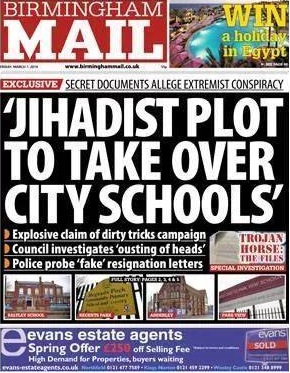

It began with an anonymous letter that is widely now believed to have been a hoax. But the Trojan horse allegations, that a group of hard-line Salafis were plotting to impose a strict interpretation of Islam in secular state schools, exploded into one of the biggest scandals Birmingham has ever seen.

There were four separate inquiries, one led by the former head of counter-terrorism in the UK, and dozens of reports in 25 schools. It also led to a political fall-out at the heart of government and contributed to the demotion of the education secretary, Michael Gove.

Every morning as they started their school day, children in the city, and their parents, had to contend with camera crews and journalists waiting outside the gates, filming them and asking for interviews.

Now a study by Birmingham City University, released exclusively to Channel 4 News, has looked at the impact this had on those children. The study, by criminologist Imran Awan, found some worrying evidence that Muslim communities have been left feeling targeted and stigmatised.

“Previous studies have shown that British Muslims felt very comfortable with their identity, they felt well integrated and proud to be British citizens,” Mr Awan told me. “But much of this has been undone by what they feel has been relentless, unfair criticism.”

One mother said: “What’s the point of us trying to integrate, every time we do we are somehow told it’s not good enough, or we’re not getting it right.”

Researchers interviewed parents, teachers, governors and local residents. Some felt that the scandal had left them feeling that everyone was looking at them and pointing at them as they walked down the street. One resident claimed that her neighbours had stopped talking to her as a result, adding: “In fact we have seen rubbish thrown in our front garden… We have all been labelled extremists and radicals.”

A huge concern was the impact of these labels on children. “What happens when they go for a job, or try to get work experience, and employers read that they’re from one of these so-called extremist schools,” asked a teacher.

Although the official reports into some of the schools raised important concerns about governance, many Muslims feel this would have been dealt with differently if they hadn’t been mainly Muslim pupils. A common complaint I heard when I was out reporting on the story was that Muslims now feel they are like the new Irish.

The study suggests it will be difficult to convince some parents to support changes needed in some of the schools, which may make them harder to implement.

In 2007, David Cameron stayed with a Muslim family in Birmingham and said they had taught him about British values and that lazy stereotypes about Muslims and terrorism would damage community cohesion.

“Indeed, by using the word ‘Islamist’ to describe the threat, we actually help do the terrorist ideologues’ work for them…” he said at the time.

“It is ironic that this is exactly the kind of language still being used to describe the Trojan Horse plot,” said Mr Awan. “A fact not lost on many in Birmingham.”

See also “‘Trojan Horse extremism myths damaging community cohesion in Birmingham’ – study finds”, Birmingham City University news report, 24 July 2014

Update: See “Communities ‘have been damaged by Trojan Horse scandal'”, Birmingham Mail, 27 July 2014